His offer to found a “scholar’s society” at the 1825 Parliament made Széchenyi famous overnight. He had no concrete plans at the time, but after the Diet he became increasingly active in public life. His main aim in modernising the underdeveloped country was to win over those who could do the most to achieve this, namely his fellow aristocrats. In order not to discourage them, he wanted to take only small steps along the path of bourgeois transformation.

In his theoretical works published in the early 1830s, he set out his programme for the modernisation of Hungary, the non-violent abolition of the feudal order, which had reached crisis stage, and the gradual establishment of a bourgeois society and a capitalist economic order. His works played an enormous role in the national awakening of the 1830s, and in the emergence of a powerful liberal reform movement among the nobility. He was the first to formulate the theoretical foundations of this movement and many of its concrete reform initiatives – emancipation of the serfs, public taxation, equality before the law, etc. – and to formulate the first concrete proposals for reform.

However, Széchenyi saw the transformation as only possible with the support of the aristocracy and the imperial government. He was so confident in the power of common sense that he took it for granted that, with sufficient caution, the main beneficiaries of the existing order could be persuaded to support the inevitable reforms.

The strong opposition reform movement, which also opposed Vienna, discouraged him to some extent. He believed that the militant opposition party led by Lajos Kossuth was jeopardising the success of his initiatives and was leading the country into a revolution that threatened to bring disaster. The passionate debate between Kossuth and Széchenyi, which lasted until 1848, became the most famous intellectual duel in the history of Hungarian political thought, obscuring for posterity the important fact that the main frontline was not between the two, but between the conservatives in the governing party, who insisted on maintaining the system unchanged and the liberals, who advocated ‘regime change’. Both of them envisioned a transformation of Hungary based on the ideas of liberalism, but at different speeds, with different means and at different depths.

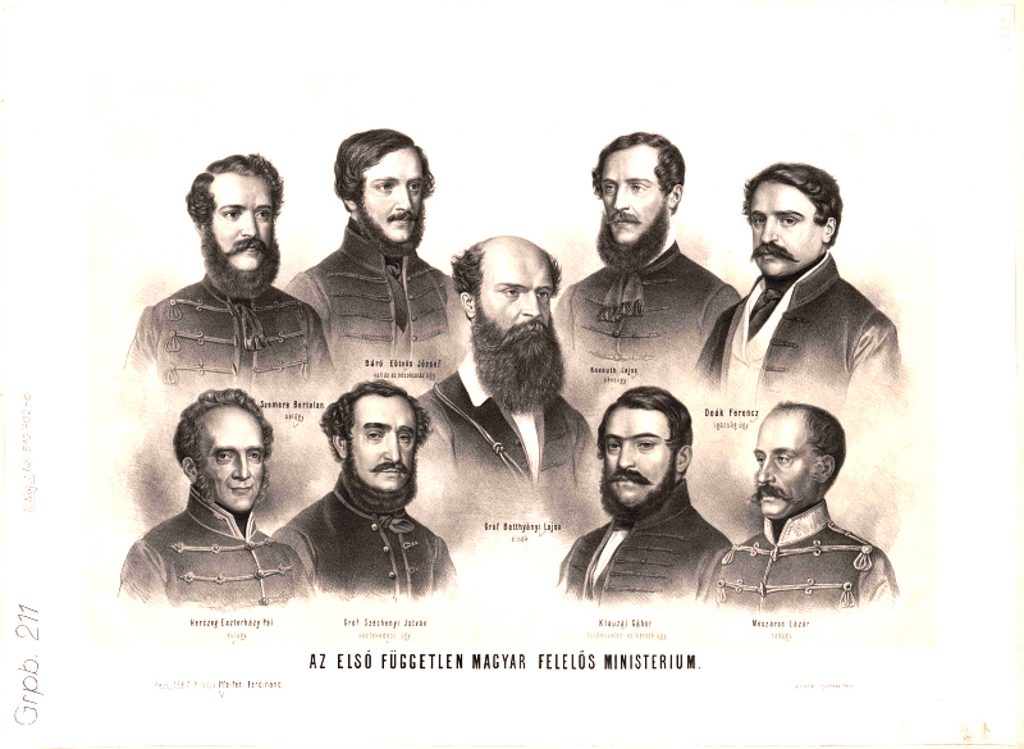

With the polarisation of the reform opposition, Széchenyi found himself in relative political isolation, from which he was freed by the revolution of 1848. In the weeks after the revolution, he used his personal influence to fight for the ratification of the laws of bourgeois transformation in Vienna, and then took over the leadership of the Ministry of Transport in the first independent, responsible Hungarian ministry.