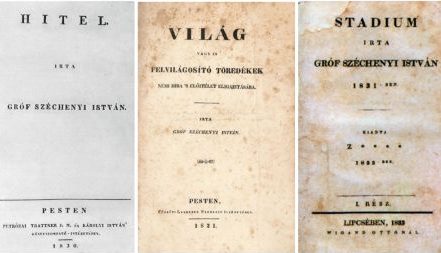

After one or two unpublished works Széchenyi went public in January 1830 with his epoch-making work, Hitel (Credit). In this work, and in the following works of his great trilogy, The World and The Stage, he outlined a programme for the modernisation of Hungary, the non-violent abolition of the feudal order, which had reached crisis point, and the gradual establishment of a bourgeois society and a capitalist economic order. His works played an enormous role in the national awakening of the 1830s, and in the emergence of a powerful liberal reform movement among the nobility. He was the first to develop the theoretical foundations of this movement and many of its concrete reform initiatives – emancipation of the serfs, public taxation, equality before the law, etc. – and to formulate the first concrete proposals for reform.

He first voiced his concern about the opposition party, which was increasingly dominated by Lajos Kossuth, and called for a faster and deeper transformation than his own, with his pamphlet The People of the East in 1841, thus starting the passionate Kossuth-Széchenyi debate that lasted until 1848. During these years, the newspaper Jelenkor was his main mouthpiece.

After regaining his intellectual faculties, he also started writing in Döbling, partly “for therapeutic purposes”, for himself, partly for the public. The highlight of his publicistic activity at this time was his anonymously published Ein Blick, a scathing critique of the Bach system.